Yellow Sigatoka (leaf spot) Pseudocercospora musae

What is yellow Sigatoka and where does it occur?

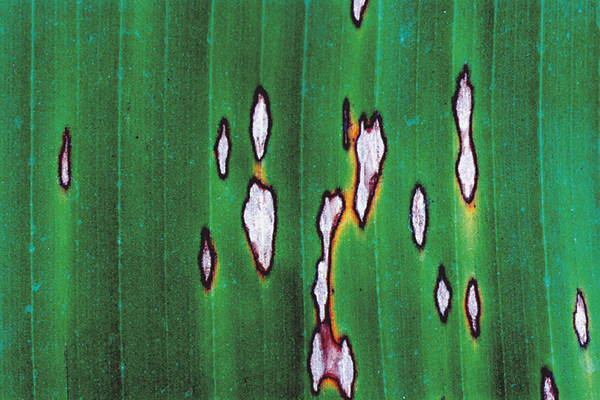

Yellow Sigatoka is a fungal disease in bananas that causes leaf lesions and is commonly referred to as leaf spot. The fungal plant pathogen that causes the disease is Pseudocercospora musae.

Yellow Sigatoka occurs in all growing regions of Australia and is common in Far North Queensland, particularly during the wet season when conditions are warm and moist.

How does yellow Sigatoka impact banana production?

The lesions caused by the disease result in premature leaf death and reduces the plant’s ability to photosynthesize, impacting bunch size and delaying bunch filling. It also reduces the green life of fruit, causing mixed ripening which can restrict market access.

If left uncontrolled or unmanaged (Figure 1), costs of deleafing and spraying increase and it can be difficult to identify other exotic leaf diseases such as black Sigatoka.

How does yellow Sigatoka spread?

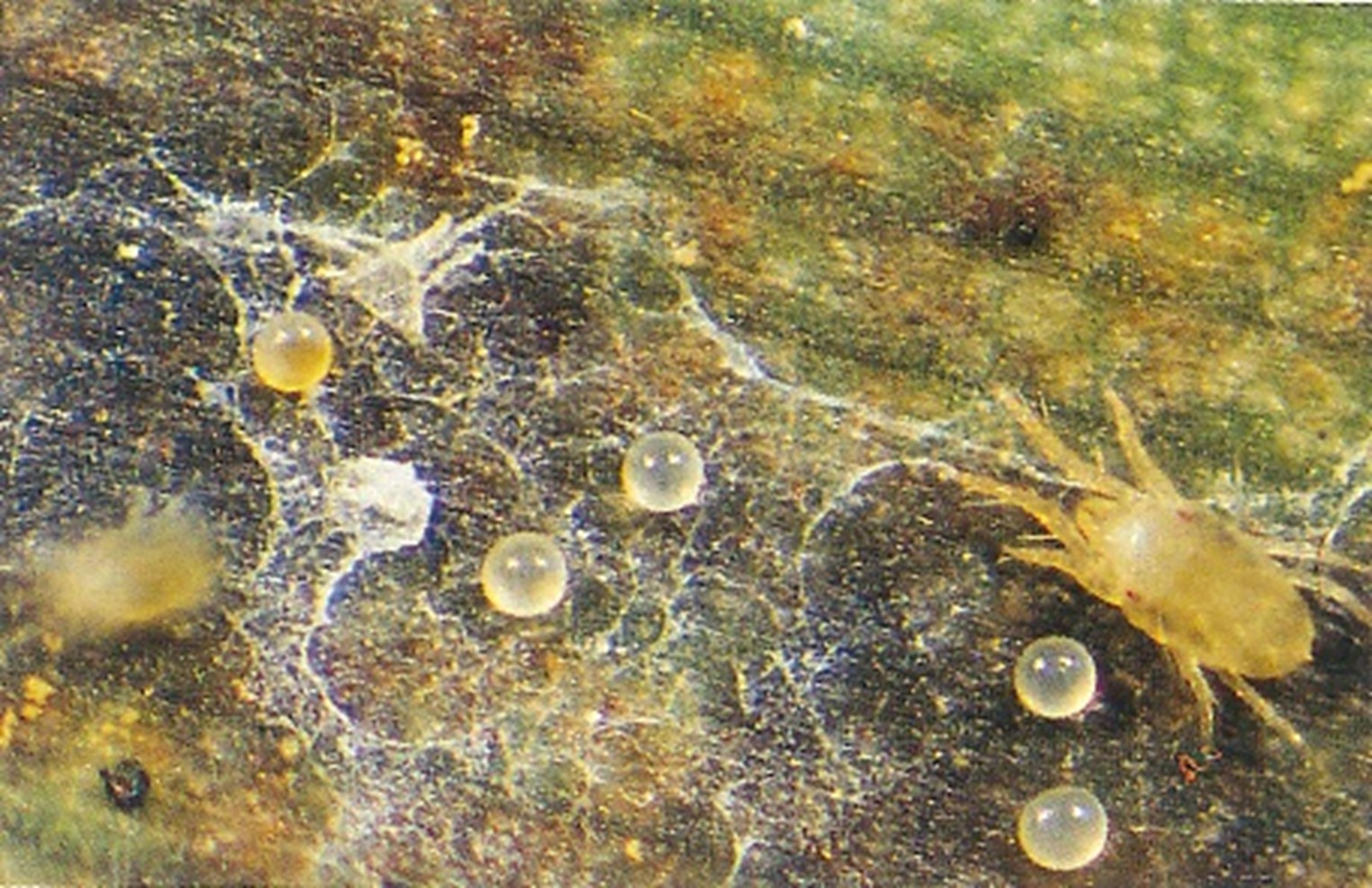

The disease produces two types of spores, ascospores and conidia that spread by two main vectors, air and water.

Air movement within banana paddocks allows for easy dispersion of fungal spores (ascospores), allowing them to settle and infect new plants. These spores are most active in the wet season due to warm and moist conditions, causing tip spotting in younger leaves. Ascospores are responsible for the long distance spread of the disease due to dispersing in air currents.

Movement by water, such as rainfall or dew, moves conidia from higher leaves down the plant and onto suckers and causes line spotting on the leaf. Conidia infect new leaves of the same plant or neighbouring plants if the rain is wind driven.

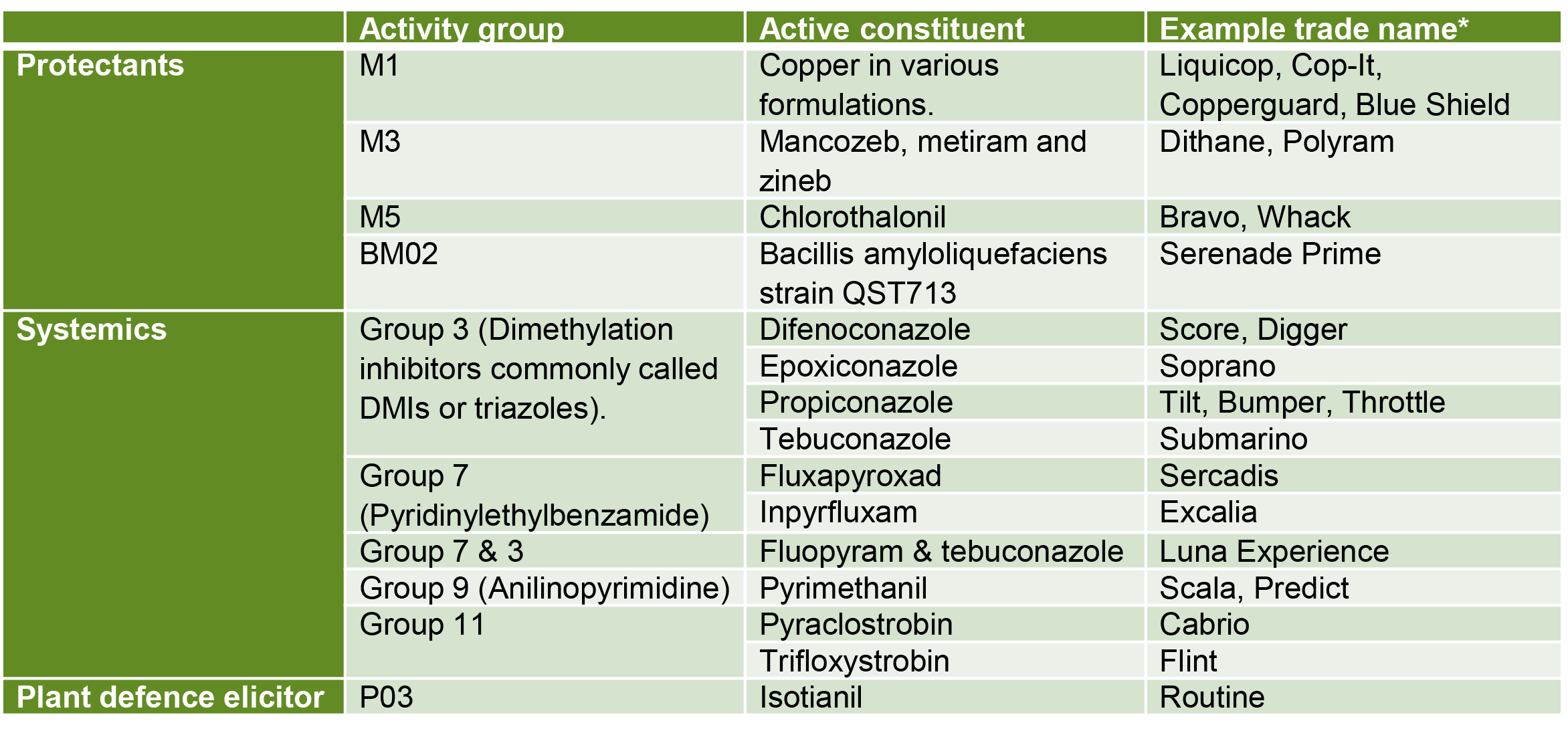

What are the stages of yellow Sigatoka

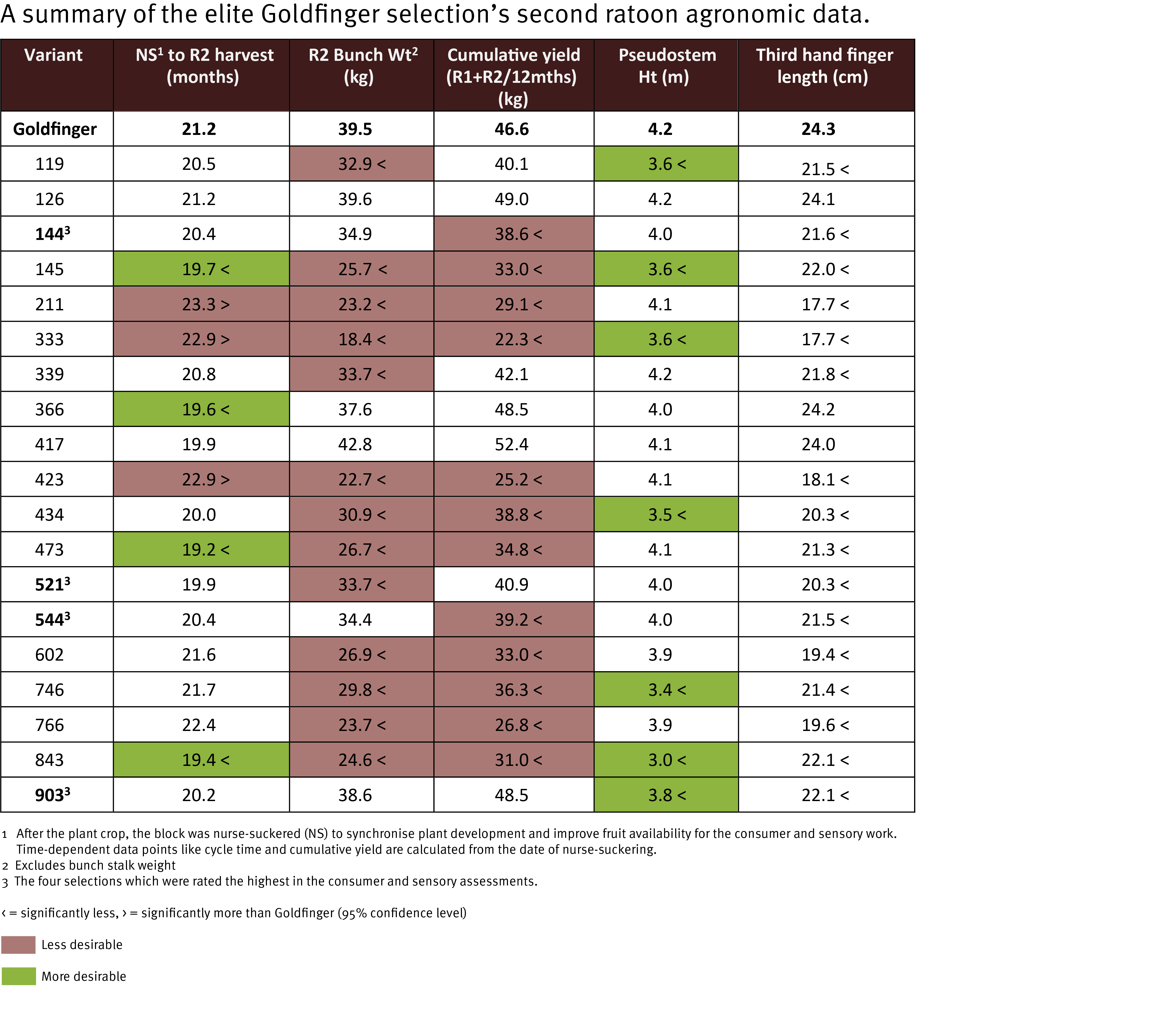

Symptom development of yellow Sigatoka is broken up into five stages (Figure 2).

Stage 1: Yellowish green specks less than 1mm long. Generally, younger leaves are affected. Very hard to see with the naked eye.

Stage 2a: Specks develop into yellow streaks 3 to 4 mm long.

Stage 2b: Streaks darken to a rusty brown.

Stage 3: Streaks broaden to a spot, becoming wider with undefined margins.

Stage 4: Spots develop defined dark brown edges, the centre becomes sunken and occasionally has a yellow halo. Conidia are produced on stage 4 lesions.

Stage 5: Sunken centre turns grey and is surrounded by dark brown/black border. Ascospores are produced on stage 5 lesions.

How is yellow Sigatoka managed?

Yellow Sigatoka can be difficult to control in wet, moist conditions and should be managed with a combination of cultural and chemical controls.

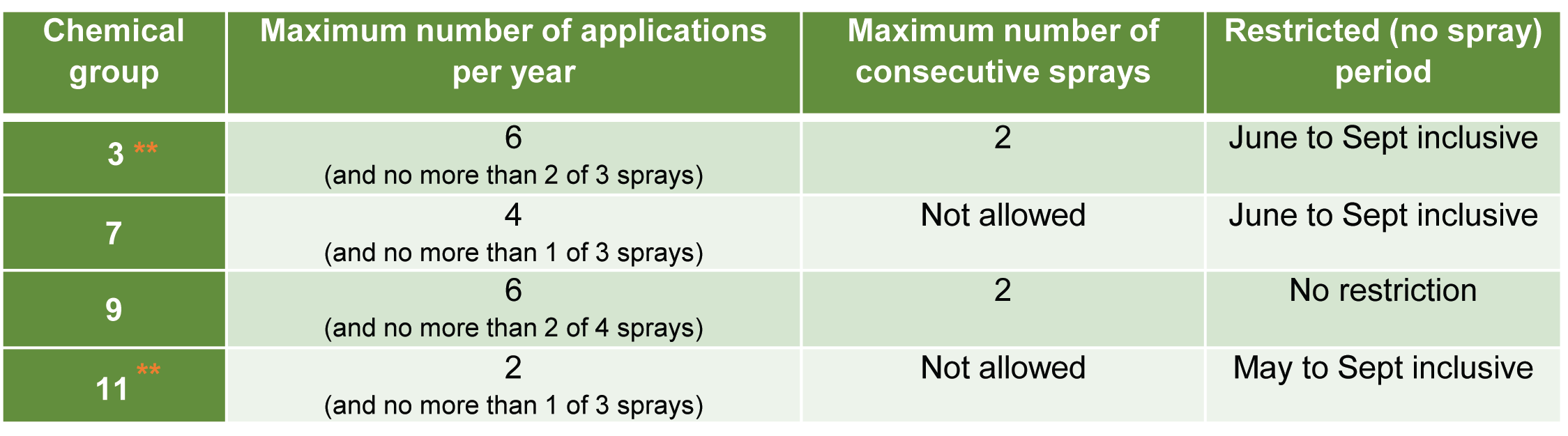

Deleafing (Figure 3) is a major component of managing yellow Sigatoka that cannot be overlooked. Increased chemical application is unable to compensate for regular deleafing practices.

What cultural controls should I practice?

Controlling yellow Sigatoka is best managed through cultural control practices. Although labour intensive, they are necessary to keep fungal levels low within a canopy, especially during periods of high rainfall when the ability to aerial spray or mist is limited.

Deleafing is the most critical control method for managing yellow Sigatoka.

Deleafing removes infected leaves from the canopy and assists in keeping disease inoculum levels low. Deleafing is recommended once a single leaf on a plant has leaf spot lesions on more than 5% of the total leaf surface.

To prevent yellow Sigatoka infections, some growers practice intensive deleafing practices. This involves removing additional leaves, that are not yet showing visible signs of the disease, as the early stages can be difficult to detect with the naked eye. Bunched plants are an exception, as most growers only remove the minimum number of leaves. Tipping, which is only cutting out a proportion of the leaf with visible symptoms, is not recommended as the entire leaf would be infected.

Deleaf before spraying, as once yellow Sigatoka produces visible lesions (stage 3 onwards) neither systemic nor protectant fungicide applications are effective against those spots. Deleafing also assists in reducing the risk of fungicide resistance on your farm, and neighbouring farms.

Recent research suggests that the best deleafing practice is to go through frequently before the wet season to get inoculum levels low. This will improve spray efficiencies before the warm wet summer when yellow Sigatoka pressure is heaviest. In the wet season, deleafing can extend to every 6-8 weeks and during the dry season every 8-12 weeks, depending on disease pressure.

Other cultural practices

Other cultural practices, such as block design, are also important for managing the disease. Maximising airflow through a block will assist in creating conditions that minimise disease development. This includes the following considerations:

Avoid placing blocks close to waterbodies, such as dams, as it will only promote the disease due to the high humidity associated with them.

Lower density plantings are recommended to promote a drier microclimate.

Maintain good drainage to ensure water does not sit within interrows.

Reduce plant-to-plant contact by removing unnecessary suckers.

Download this information as a factsheet

More information

Videos

Overview of leaf spot diseases and their impact

Yellow Sigatoka – Life cycle and how it spreads

Yellow Sigatoka – Management tips for growers

For more information contact:

The Better Bananas team

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

South Johnstone

13 25 23 or email betterbananas@daf.qld.gov.au

This information has been produced as part of the National Banana Development and Extension Program, funded by Hort Innovation, using the banana research and development levies and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture. The Queensland Government has also co-funded the project through the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.