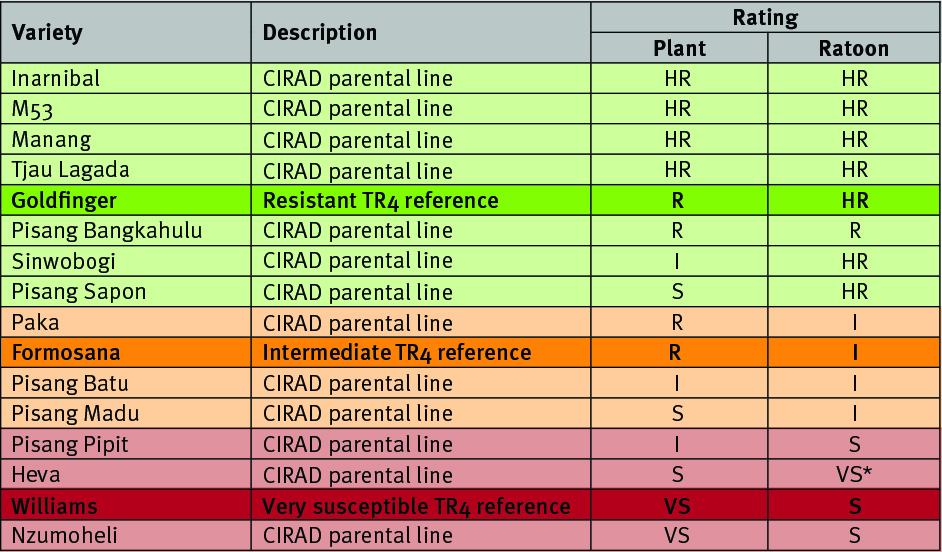

Highly resistant and resistant

The four parental lines – Inarnibal, M53, Manang, and Tjau Lagada, were highly resistant in both the plant crop and first ratoon, with no symptoms of TR4 infection. One of the Goldfinger plants (TR4 resistant reference) expressed disease symptoms resulting in the death of the mother plant, yet no disease symptoms were observed in the subsequent ratoon crop for the same plant or any of the other Goldfinger ratoon plants. Mild disease symptoms were observed for Pisang Bangkahulu

in the plant crop and this was repeated in the first ratoon.

Surprisingly, the two varieties, Sinwobogi and Pisang Sapon, made a major recovery – with no disease symptoms in the ratoon, compared to the plant crop where the disease was clearly prominent.

Intermediate

In the case of Formosana and Paka there was an increase in the number of diseased plants in the ratoon crop cycle, moving them into the intermediate category. Pisang Batu retained its intermediate rating whereas some improvement was observed in Pisang Madu where fewer diseased plants were noted in the ratoon crop cycle compared to its susceptible plant crop cycle.

Susceptible and very susceptible

The most susceptible lines were Heva and Nzumoheli, which were the most susceptible of the parental lines in both crop cycles, consistent with the Williams TR4 reference variety. Pisang Pipit showed an increase in disease symptoms in the first ratoon crop moving it into the susceptible category.