Spider mites

Life cycle and behaviour

Both the banana spider mite (Tetranychus lambi) and the two-spotted mite (Tetranychus urticae) are often simply referred to as ‘spider mites’. Both are common pests of a broad range of crops and are widely distributed.

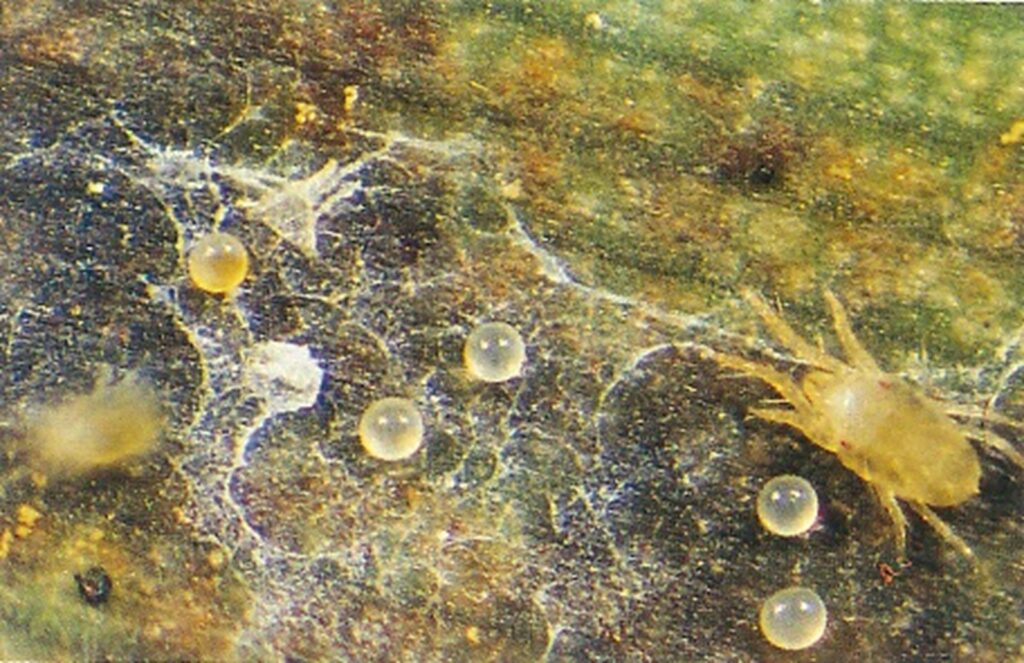

The life cycle and appearance of the banana spider mite and the two-spotted mite are similar. Both mites are typically found on the underside of leaves, only being present on the top side in very high infestations. The main distinguishing feature between the two types of mites is that high populations of the two-spotted mite are always associated with webbing (similar to spiders), while this is absent in infestations of the banana spider mite. Webbing occurs near mite colonies, typically on the underside of the midrib or in severe infestations, down the leaf veins. The two-spotted mite is more commonly found on bananas in South-East Queensland and northern NSW. By comparison, the banana spider mite predominantly is in Far North Queensland and is also identifiable as it is more straw coloured and lacks spots.

The straw-coloured or greenish adult banana spider mites are usually less than 0.5mm in length and are best seen with the aid of a magnified (10X) hand lens. Under good light, the eight-legged adults have a spider-like appearance that can just be made out with the naked eye.

The very small transparent to yellow, spherical eggs are laid singly on the leaf surface and, upon hatching, pass through two nymphal stages before becoming adults. In hot conditions, the life cycle can be as short as seven to ten days.

By comparison, the adult female of the two-spotted mite (T. urticae) lives two to four weeks and can lay several hundred eggs during her life.1 Their quick life cycle and the ability of females to produce many eggs, can mean populations build rapidly if conditions are favourable.

Spider mites mainly use wind and small spun lines of web to migrate. The two-spotted mite is known to travel in winds as low as 8 km/h but prefers stronger winds.2 Mites also have the ability to move by walking on or short distances between plants2. Spider mites can migrate at any time, tending to move on when their populations become high, predators become abundant or the quality of food sources declines.

References

- Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry 2009, University of Florida, viewed 17 January 2022, https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/orn/twospotted_mite.htm#top

- Seeman, O, Beard, J 2005, National Diagnostic Standards for Tetranychus Spider Mites, Plant Health Australia, Canberra

For more information contact:

The Better Bananas team

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

South Johnstone

Email betterbananas@daf.qld.gov.au

This information is adapted from: Pinese, B., Piper. R 1994, Bananas insect and mite management, Department of Primary Industries, Queensland

This information has been prepared as part of the National Banana Development and Extension Program (BA19004) which is funded by Hort Innovation, using the banana industry research and development levies and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture. The Queensland Government has also co-funded the project through the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.