Grower case study

Reinventing the pod

Spray down with the Randhawa brothers

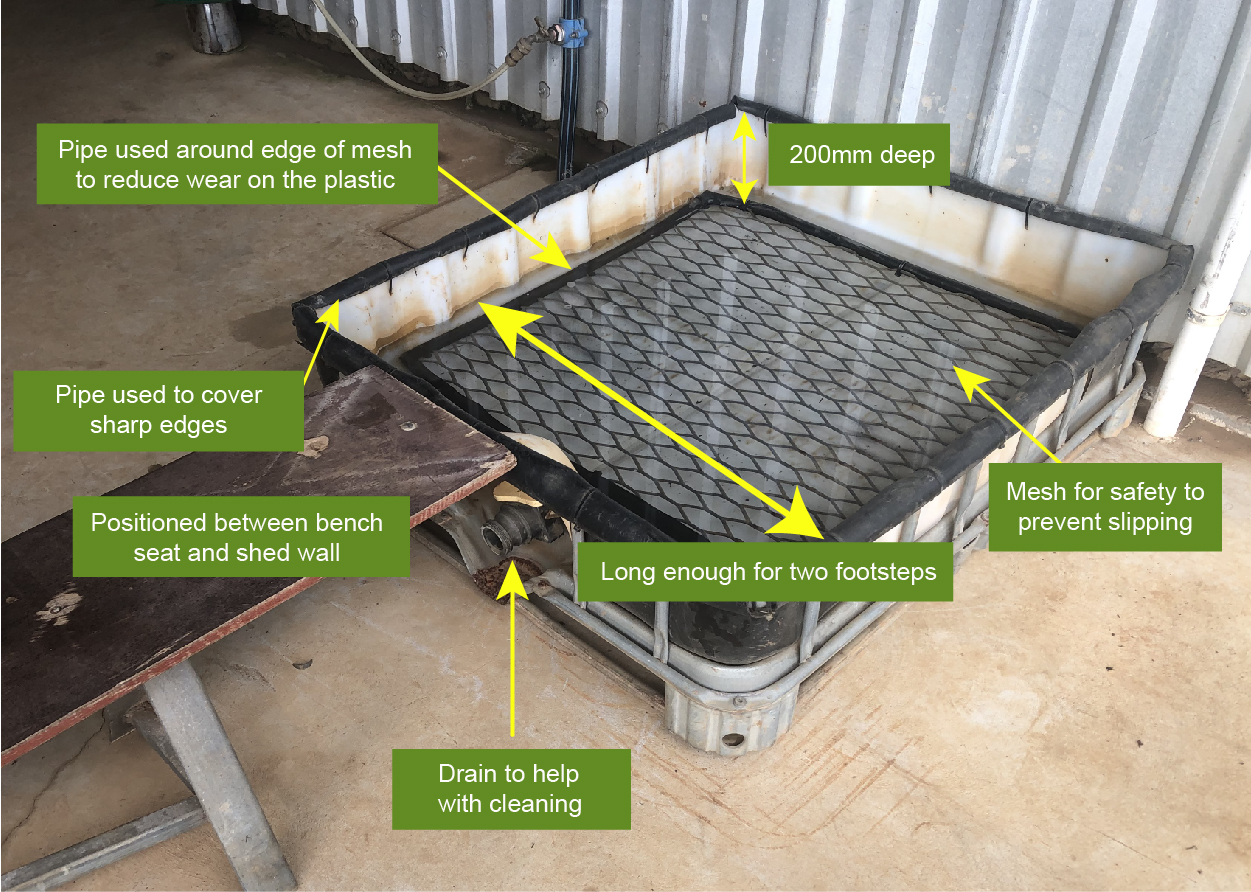

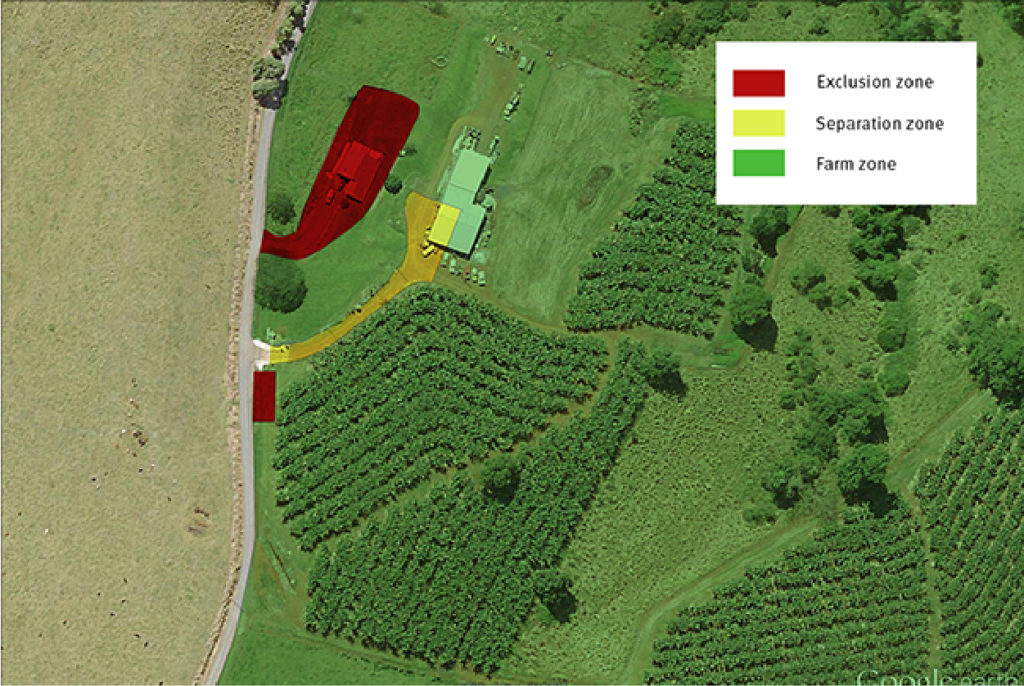

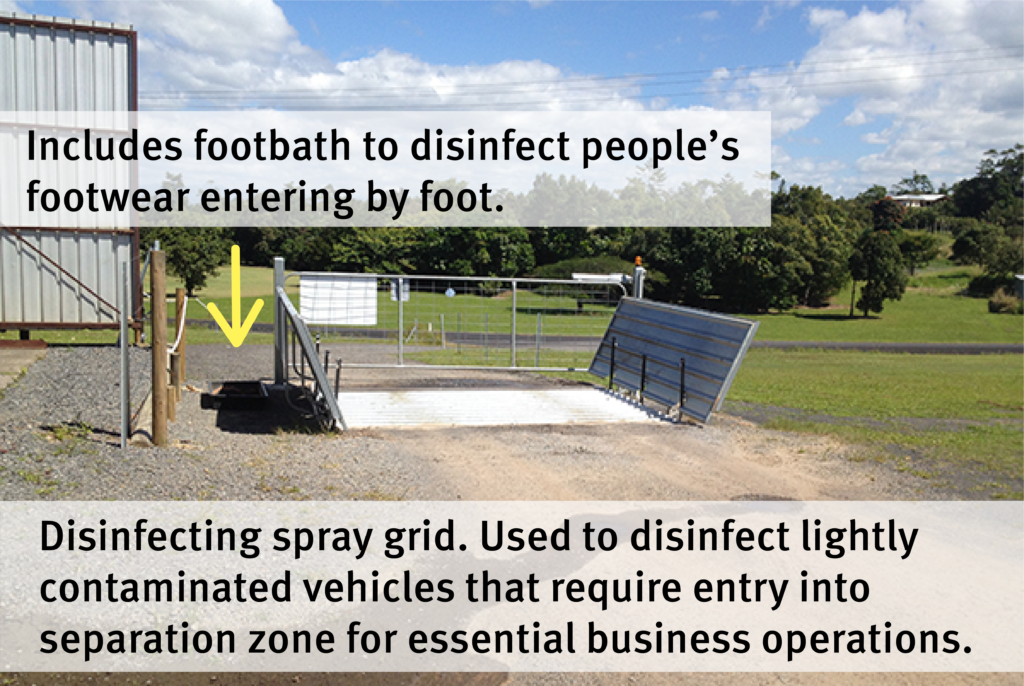

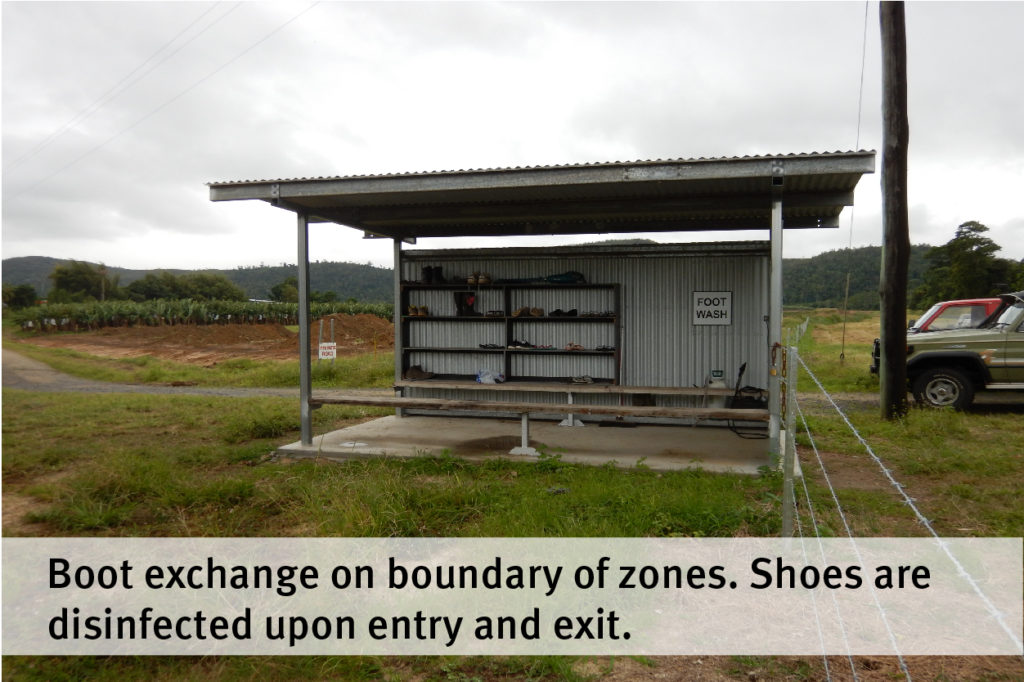

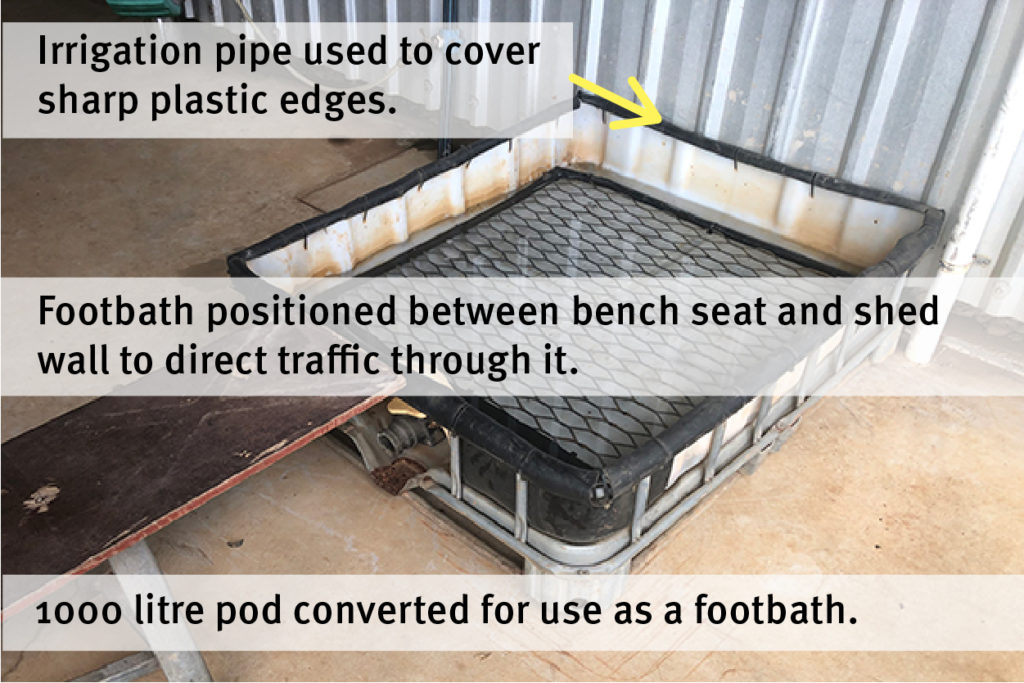

1000 litre pods can be useful in many ways. After Panama disease tropical race 4 (TR4) was found in Tully, brothers Paramadeep and Harpreet Randhawa, like many banana growers, recycled one to use as a disinfectant spray down unit at the entrance to their farm.

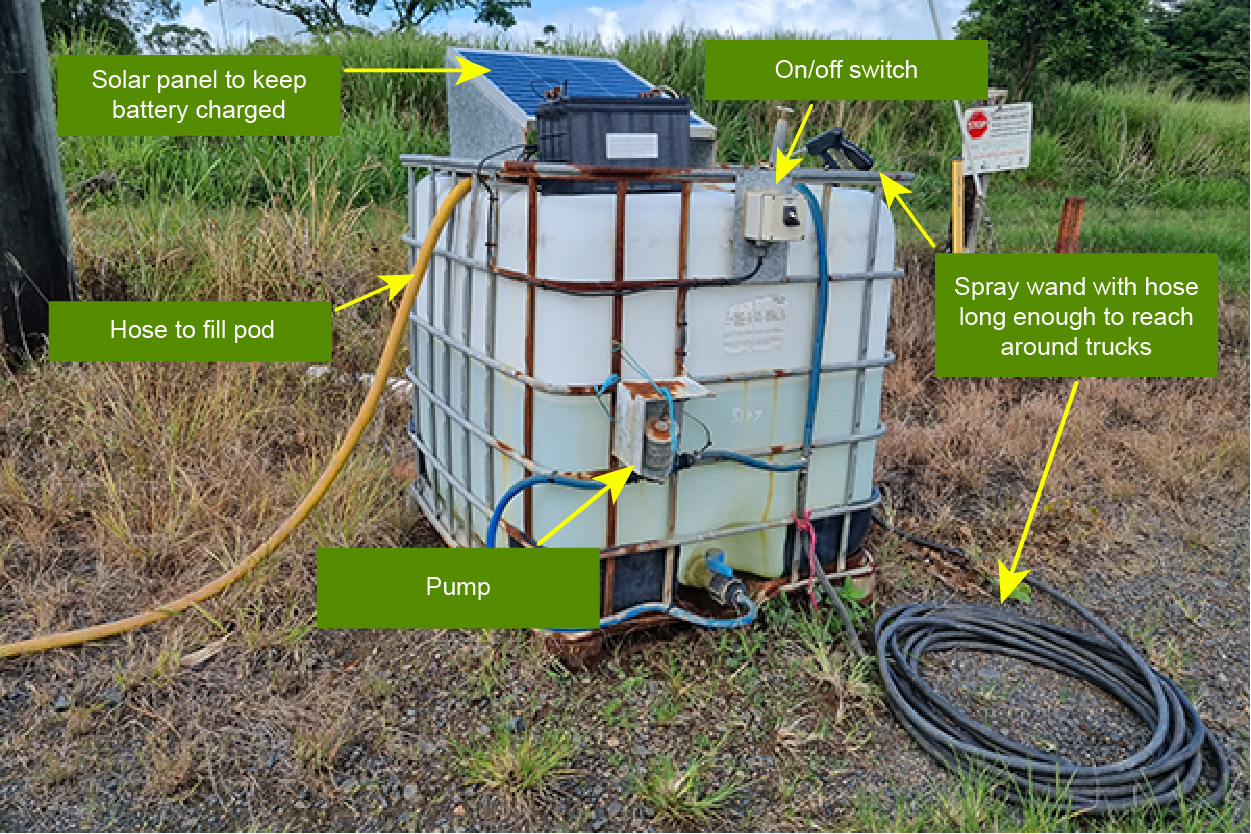

Paramadeep and Harpreet Randhawa started growing bananas in 2015, the same year that Panama disease TR4 was found in Tully. To help protect their farm, they purchased a pod from a local fertiliser distributor and engaged a local electrical contractor to install a 12-volt pump, hose and spray wand. They used a spare tractor battery to power the pump and installed a solar trickle charger to keep it charged. The whole setup cost around $500 at the time.

Harpreet said, ‘We placed the pod right at the start of the driveway to our shed. The position of the pod is good as I can see it from the packing shed, so I can make sure everyone that comes onto the farm sprays their vehicle down.’ In busy times the pod lasts about a month, so Harpreet tops up the pod with fresh disinfectant mixture as required.

Paramadeep and Harpreet use a quaternary ammonium based disinfectant product which has been shown to be effective in killing the fungal spores that cause Panama disease. They have also installed a water supply to make refilling the pod easier.

The only hitch the brothers have come across is the solar panel doesn’t keep the battery charged when there are long periods of overcast wet weather. On these occasions they just take the battery back to the shed to charge it.

Paramadeep said ‘Make sure that the hose is long enough to be able to spray all around the longest truck that comes onto your farm. We have found that most people that come to our farm follow our instructions to spray down to help us to protect our business.’

Thank you to Paramadeep and Harpreet Randhawa who provided their time and gave permission to use this case study for the benefit of the wider industry.

Tips on disinfectants!

-

Use disinfectant products containing Didecyl dimethyl ammonium chloride (DDAC) or Benzalkonium chloride (BZK). These quaternary ammonium (QA) compounds have been tested and solutions mixed as per the label rate do kill the fungal spores that cause Panama disease.

-

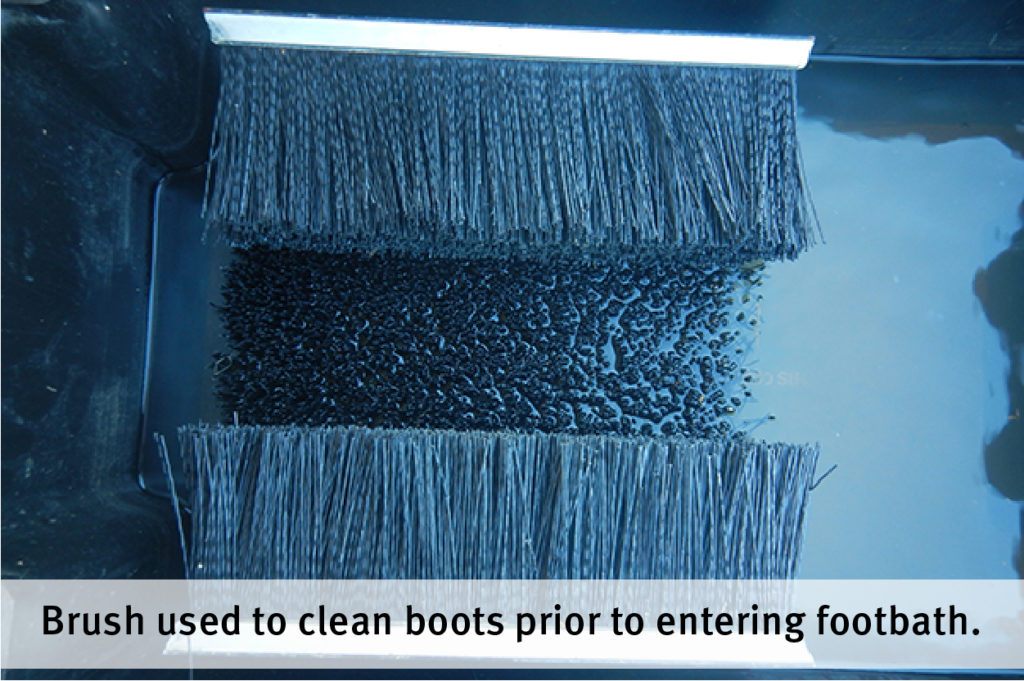

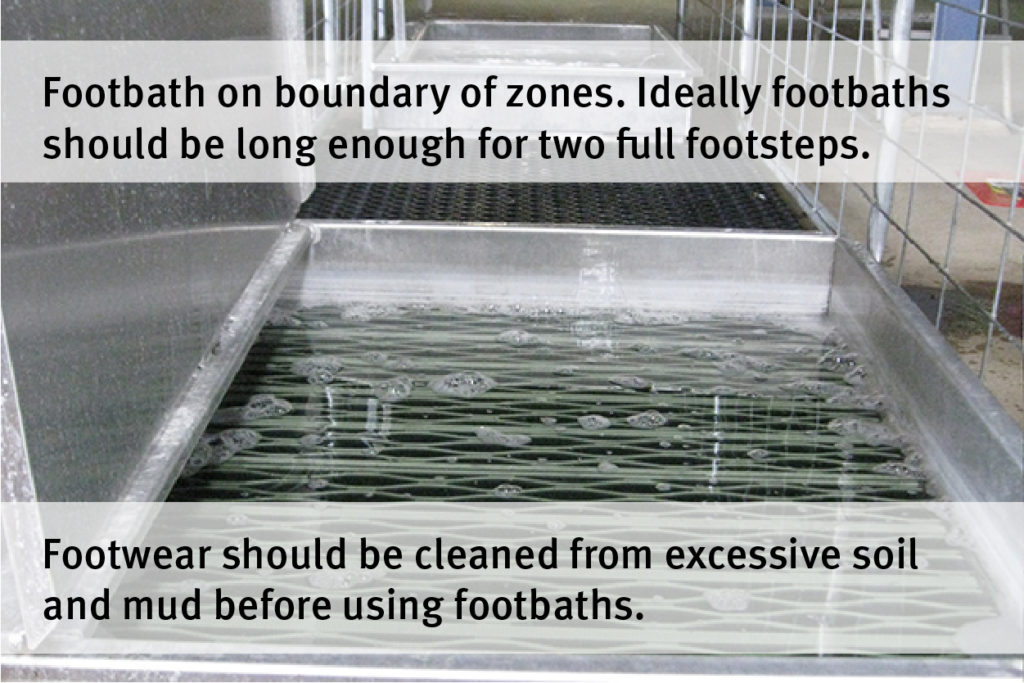

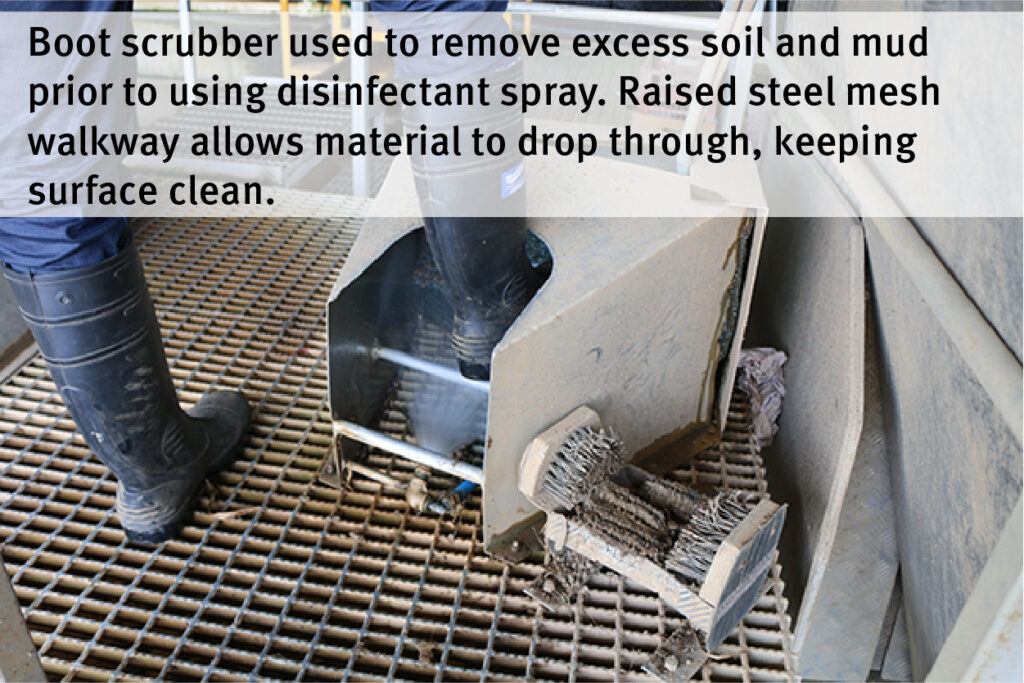

It is important to remove all soil and organic matter before applying any disinfectant product.

-

Research has shown that DDAC and BZK disinfectants used in infrastructure such as spray shuttles, that isn’t contaminated with soil and organic matter, will be effective for an extended period of time when exposed to outdoor conditions.

-

Easy-to-use test strips can be used to regularly test QA concentration of solutions in footbaths, spray shuttles and wash-down facilities.

Click here for information on disinfectants.

If you would like further information or assistance with setting up or improving biosecurity practices for your farm, please contact the National Banana Development and Extension Team on email betterbananas@daf.qld.gov.au or phone 07 4220 4152.

This case study has been produced as part of project BA19004 the National Banana Development and Extension Program which is funded by Hort Innovation, using the banana industry research and development levies, co-investment from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.