Unravelling the mystery of banana tips

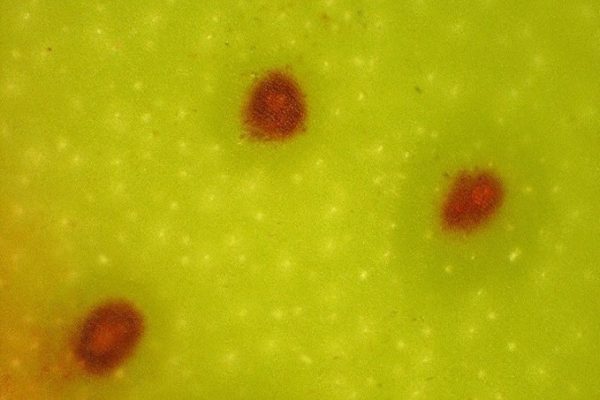

What is the black spot at the tip of my bananas? This was a question recently asked by a grower. The DAF extension team set out to investigate the issue and find out the cause.

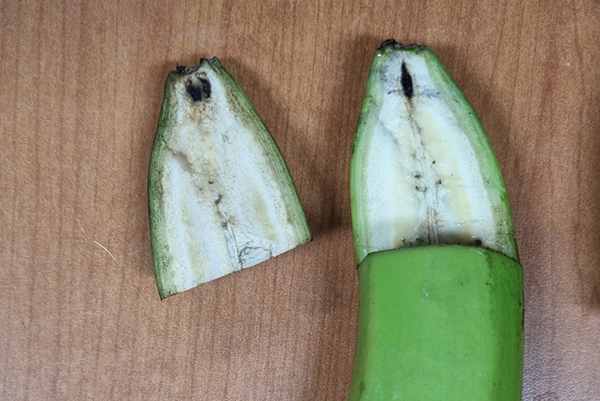

It was suggested that the discoloration could be Mokillo disease, a bacterial infection that causes dry rot at the end of the finger, starting in the same area on the fruit that the grower was questioning. Mokillo typically only affects a few fingers in a hand, these fingers are often smaller and narrower or pinched at the tip. Mokillo infection will continue to move through the fruit over time and have a rusty red gummy appearance (internally). It was evident that the issue in question was not Mokillo given that the blackened areas were present in all examined fruit, and the symptoms did not match.

From a market perspective, the team firstly wanted to demonstrate that these black areas did not progress into the fruit pulp nor display Mokillo-like symptoms as it ripened. The extension team took a sample of mature fruit and cross sectioned them at the different ripening stages. The black tips were present in ALL of the fruit and there was no progression into the fruit throughout the ripening process. Consequently, the DAF extension team was confident that this wasn’t Mokillo.

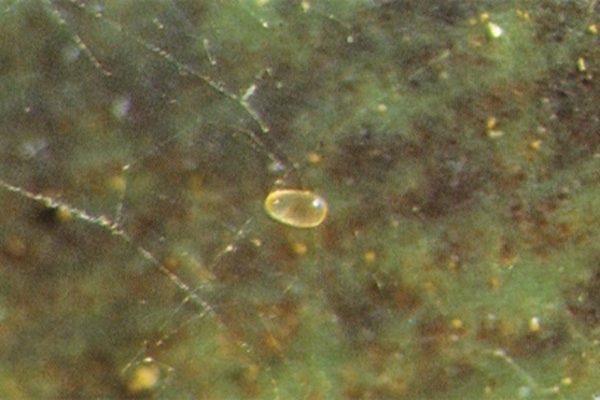

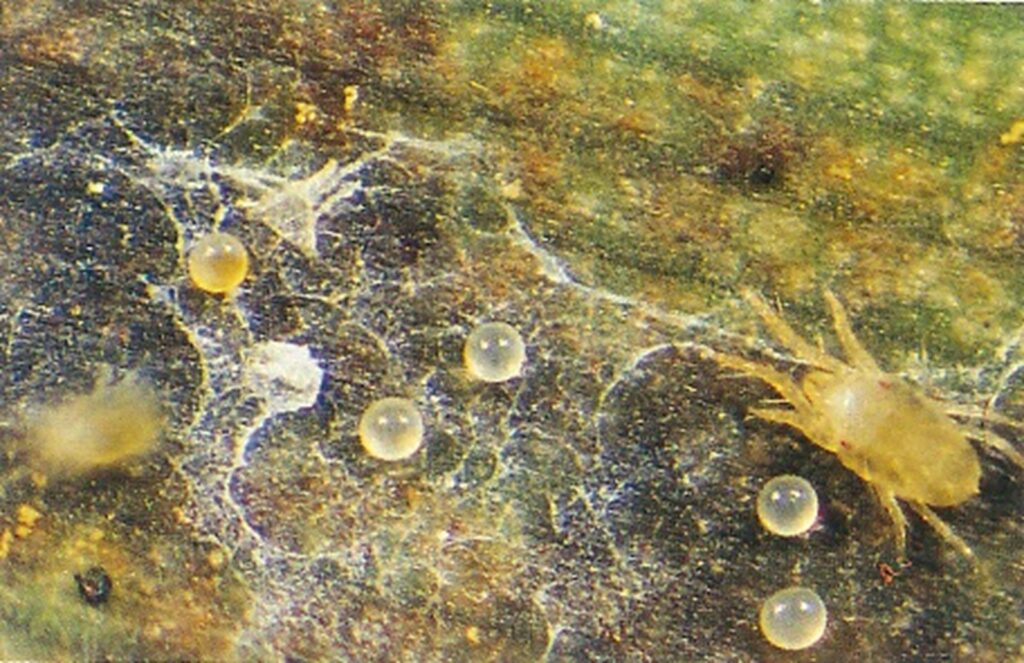

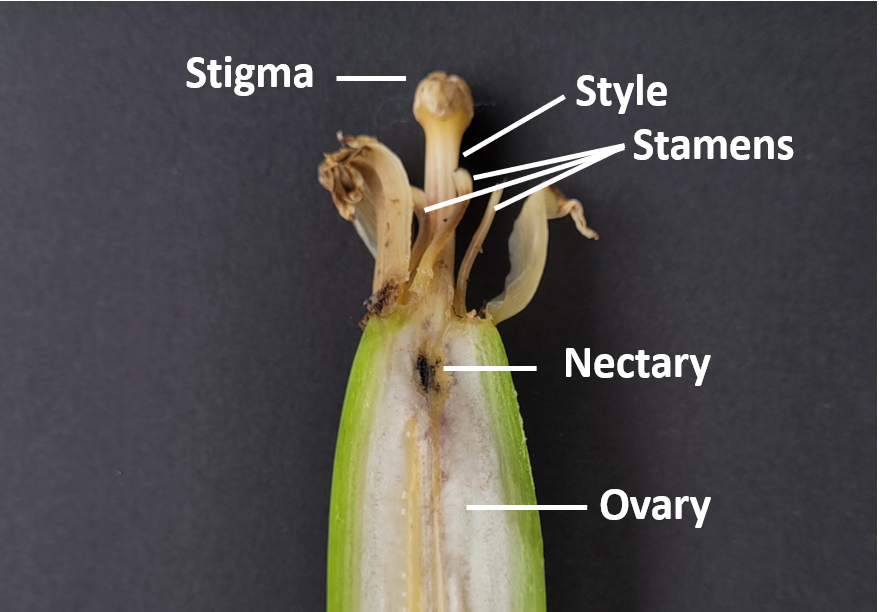

After this initial investigation, the query persisted as to the nature of this blackened internal tip. With a theory that the blackening was associated with the physical make-up of the fruit, a review of banana literature, including the basics of banana ‘anatomy’, found that this blackened area is called a nectary (Septal nectary). Nectaries are structures in plants, often found at the base of stamens (male flower parts) that provide food rewards for insect or bird pollinators and therefore play a role in the fertility of plants. Studies found that the nectary cells disintegrate/oxidise in Grand Naine when the flower ends are ‘unfurling’ allowing the reproductive structures (style and stamens) to be accessed by insects to pollinate. An interesting fact, is that this disintegrating/oxidising of the nectary acts as a ‘roadblock’ for the growth of the pollen tube towards the ovary. It has been suggested that this may be a contributing factor in why Cavendish is sterile and doesn’t produce seeds.

Overall, these nectaries which have disintegrated/oxidised don’t appear to impact fruit quality. It is possible that these areas allow for secondary infections, like Mokillo, which explains some of the similar symptoms. However, further investigations would be needed to better understand the risks and conditions which may favour these infections. The DAF extension team will continue to keep tabs on the blackening of nectaries at ad hoc times throughout the year in the course of their work and make observations in other varieties.

References

- Soares, T.L.; Souza, E.H.; Costa, M.A.P.C.; Silva, S.O.; Santos-Serejo, J.A. In vivo fertilization of banana. Ciênc. Rural 2014, 44, 37–42.

- dos Santos Silva, M.; Santana, A.N.; dos Santos-Serejo, J.A.; Ferreira, C.F.; Amorim, E.P. Morphoanatomy and Histochemistry of Septal Nectaries Related to Female Fertility in Banana Plants of the ‘Cavendish’ Subgroup. Plants 2022, 11, 1177.

This article has been compiled as part of the National Banana Development and Extension Program (BA19004) which is funded by Hort Innovation, using the banana research and development levy, co-investment from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.