Banana weevil borer Mass trapping: A novel design, supporting long-lasting pheromone lures in NSW

Banana Weevil Borer (BWB) is one of the main issues for NSW banana growers. When BWB reach high numbers in the field, they significantly affect productivity by creating a network of tunnels in the corm. This tunnelling weakens the plant and increases the likelihood of blowdowns. BWB infestations affect nutrition uptake, contributing to slow growth, decreased bunch weights and overall poor plant health. NSW growers have successfully designed and implemented mass trapping approaches to deal with this issue, a technique proven to be effective in other countries. Mass trapping reduces pest numbers by luring them, with an attractant, in large numbers to a trap that either kills them or prevents their exit. In this article, we discuss NSW growers’ implementation of mass trapping systems and their successes. Growers who use mass trapping have found it an effective tool for monitoring and successful in reducing BWB pressure and plant damage.

Background

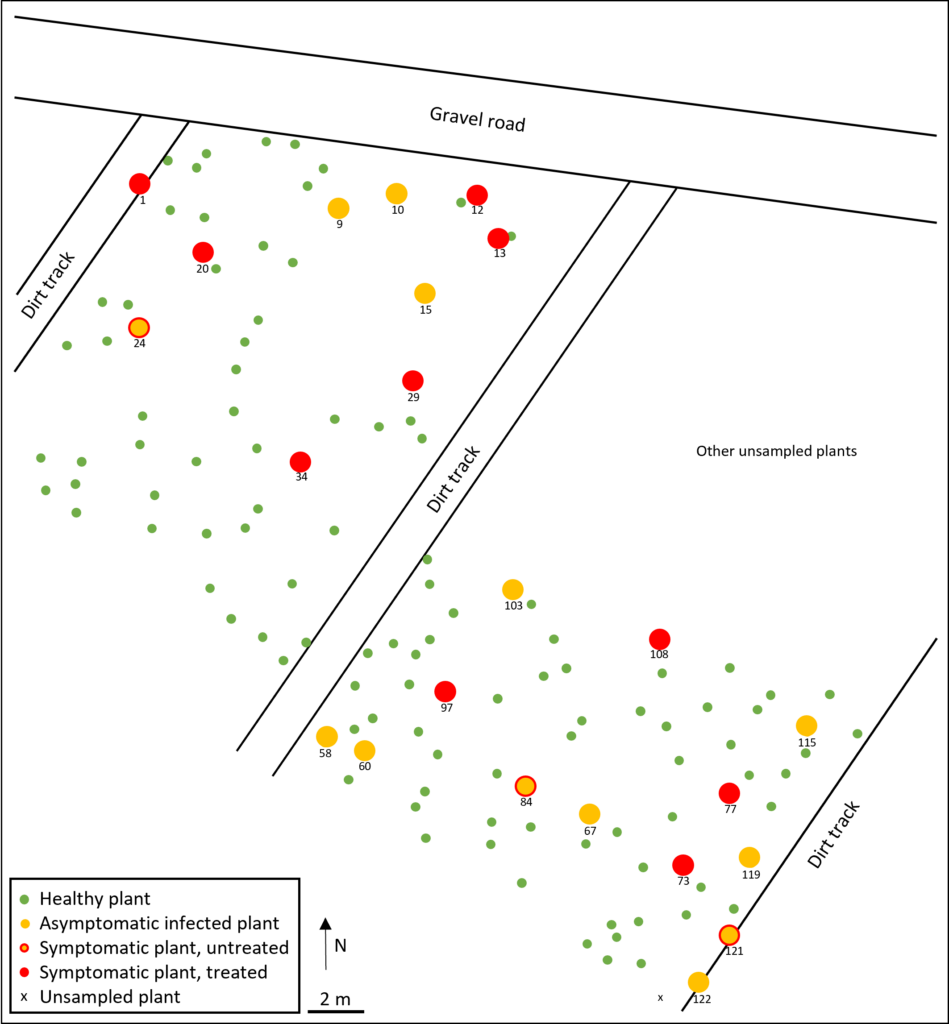

In Australia, typically pseudostem discs or small pitfall traps (less than 500mL volume) are used for monitoring and, to a lesser degree, management of BWB. These strategies are effective in allowing growers to understand their BWB populations and their distribution across their farms. By comparison, international research, and growers, have designed larger pitfall traps (larger than 500mL volumes), to increase rates of BWB capture. These larger pitfall trap designs are possible through the long-lasting pheromone lures which can and historically have also been used domestically in small-scale traps and which can attract both male and female BWB from over 20m away in dry weather. According to an international study (Alpizar et al, 2012), using these large volume mass trapping pitfall traps (with the pheromone lures), at a density of 4 traps per hectare, was 5 to 10 times more effective than traps without pheromone. In this study, corm damage was reduced by half to two thirds after several months of use (from 20-30% corm tunnelling to 10% or less). The resulting reduction of corm damage was shown to increase bunch weights of Dwarf Cavendish (Musa acuminata Colla) by approximately 20%. Trials in Australian growing regions and prominent varieties are yet to be conducted and caution is needed before assuming similar performance outcomes could be attained.

Earlier research by NSW DPI investigated two types of long-lasting pheromone lures (effective for 90 days), to determine the most effective for the NSW region. While both lures are effective at attracting BWB, Cosmolure P160-lure 90 (C.sordidus) is preferred as it does not contain isoamyl acetate, which attracts native turkeys and domestic chickens that damage the traps. Growers who collaborated in the earlier pheromone investigation have continued trapping and over time have developing unique trapping systems using the longer-lasting pheromone.

Mass trapping pitfall design 1 (5L bucket trap)

One of the new innovative methods that growers have developed and implemented is the modified 5L bucket trap. NSW growers have modified a 5-litre bucket to make large volume, mass trapping pitfall traps. To make these traps firstly, several 10-millimetre holes are drilled into the side of the bucket. Next, the bucket is firmly established into the ground. It is important that the drilled holes are flush with ground level and soil ramps need to be made (simply pile soil up into a ramp so that BWBs would be able to walk into the hole and fall into the bucket). Once the trap is established in the hill side, the pheromone bait is set by hanging from the centre of the lid via a piece of wire.

Mass trapping pitfall design 2 (PVC pipe trap)

Another innovative design that NSW growers have adopted is a PVC pipe trap. This trap is made from PVC piping which creates a narrower but deeper trap, more stabilised into the hillside compared to the larger, shallower trap, shown in design 1. In this case, the dimensions are 100mm in diameter, and 500mm in length with the bottom of the trap made watertight with end caps and the top cap left loose to be able to take off. Similar to the pitfall trap there are drilled several holes, 10mm in size, where the trap meets the soil line to allow for BWB to enter. A wire is fixed into the lid or on the side, used to hold the pheromone lure in place. The grower used an auger to install the PVC pipe approximately 300 millimetres in depth into the soil.

“I decided to increase the size of the trap purely because the original (smaller pitfall) traps were filling up in a couple of days! After increasing the size of the traps, I now only need to revisit the trap every month for soil ramp maintenance and emptying. I’m more clued in, knowing where hot spots of densely populated BWB zones were located on their farm, and using this knowledge to inform decisions around when to apply chemical management options. Something that I didn't foresee is the increased peace of mind. Now, having the traps in the ground, I see it as a second line of defence, not just relying on chemical application to control BWB, especially within the hotter and wetter periods of the year."

-Coffs Harbour grower comments on using the 5L BWB bucket trap design

Trap maintenance and upkeep

The enlarged pitfall traps require low maintenance and only need to be checked on average once per month or after severe weather events. Emptying of dead BWB will fluctuate as BWB numbers and movements vary throughout the year. According to growers, ensuring the trap stays in place, and maintaining the soil ramps up to the trap are some of the key considerations to keep an eye on and it’s suggested to check these features more regularly.

It has been a suggestion to add soapy water to the bottom of pitfall traps to terminate BWBs once they are in the trap. Furthermore, the soap makes the walls of the trap slippery, preventing them from exiting the trap. However, growers have found that this may not be necessary when the walls of the trap are smooth, as the weevils find it hard to get traction to climb out of the traps.

Cost

The P160-Lure90, Cosomolure (C. sordidus) is approximately $11 per bait (tablet) and lasts 90 days. The current advised density is 4 traps per hectare with one pheromone bait in each trap, totalling 16 pheromone baits per hectare per year. Therefore, currently in 2024, the approximate cost is $175 per hectare, per year. This does not include the material for pitfall traps or labour costs to install and maintain them which needs to be considered. Prices will vary over time. Ensure getting quotes from relevant suppliers before implementation. For some growers, this is a relatively low cost per hectare to substantially reduce BWB numbers throughout a block in NSW. The continued pursuit of trapping innovations reflects the proactive approach NSW growers are taking in BWB management, offering a promising avenue for control. If you are interested in more information about BWB mass trapping contact Steven Norman (NSW DPI Industry Development officer) for assistance.

More information on Banana Weevil Borer:

References

Fu, B., Li, Q., Qiu, H., Tang, L., Zhang, X., & Liu, K. (2019). Evaluation of different trapping systems for the banana weevils Cosmopolites sordidus and Odoiporus longicollis. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 39, 35-43

Alpizar, D., Fallas, M., Oehlschlager, A. C., & Gonzalez, L. M. (2012). Management of Cosmopolites sordidus and Metamasius hemipterus in banana by pheromone-based mass trapping. Journal of chemical ecology, 38, 245-252.

This information has been produced as part of the National Banana Development and Extension Program (BA19004). This project has been funded by Hort Innovation, using the banana research and development levy with co-investment from the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, New South Wales Department of Primary Industries and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.