Why is banana bunchy top disease so hard to eradicate?

By Dr. Kathy Crew and Dr. John Thomas

Banana bunchy top disease (BBTD) occurs in many locations throughout northern NSW and southern Queensland. The disease was first recognised in Australia in 1913 and by the mid-1920s had devastated the Australian industry, which was based in this region at that stage, causing losses of 90 to 95% of production. The research work of Charles Magee at the time revealed that the disease was caused by a virus (banana bunchy top virus, BBTV) which was transmitted by the banana aphid and in infected planting material. He devised a successful control program which enabled the resurrection of the industry. His strategy of inspection, destruction of infected plants, use of clean planting material, and quarantine remains the basis of BBTV control to this day.

However, despite the generally low incidence of BBTD in the region today, occasional flare-ups still occur, and the virus has rarely been eradicated from a district. Despite the low incidence in many subtropical plantations, the virus remains a potential threat to the banana industry. Why is this so?

In his research, Magee was only able to transmit the virus by aphids when they fed on a symptomatic leaf. Excellent subsequent epidemiological and computer modelling work by Rob Allen predicted that aphids were only likely to spread the virus after about four new leaves had been formed on the newly infected plant. This allowed enough time for the infected plant to develop symptoms and for the aphid vector to acquire enough virus to be infective. The BBTD control program is based on inspection intervals timed to allow the location and eradication of most infected plants within this window.

The strategic levy investment project “Understanding the role of latency in Banana Bunchy Top Virus symptom expression” (BA19002) is part of the Hort Innovation Banana Fund. As part of BA19002, we have been studying an outbreak of BBTD on a plantation in northern NSW where the disease persists at a high level, despite the control program.

By selecting “hot spot” areas in the plantation and carefully inspecting all plants in the area individually, stem by stem, we have shown that the inspectors’ high rate of positive identifications (>80%) is being maintained here. However, using laboratory tests on leaf samples from these plants, we found that BBTV was detectable in some recently infected plants before they showed symptoms. In other plants, the virus was detected in the symptomless leaf formed immediately prior to the first leaf to show symptoms.

This should not be a concern for disease spread if the virus was not transmitted from these symptomless, but infected, leaves. However, to our surprise, when we fed aphids on these leaves, the virus was transmitted to healthy banana plants. Furthermore, the rate of virus transmission was similar regardless of whether the aphids fed on infected leaves with symptoms or without symptoms.

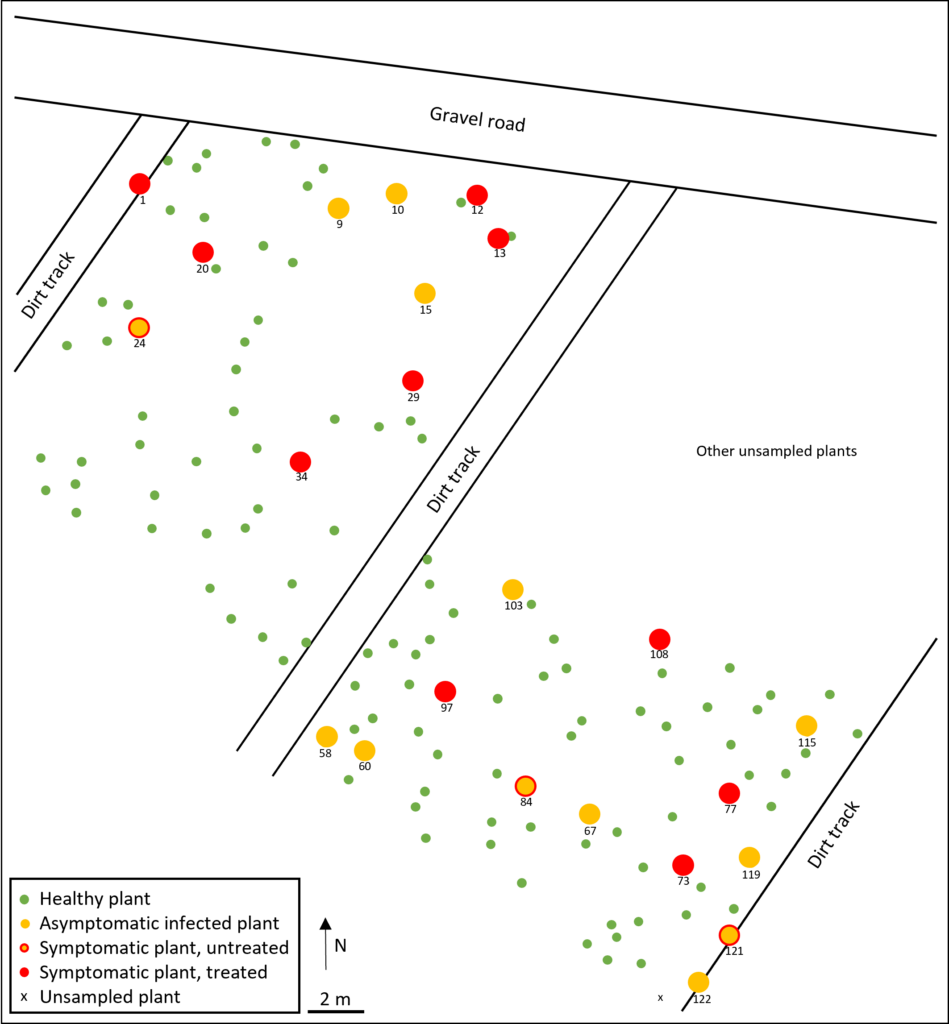

The map shows a survey area where symptomatic (red) and pre-symptomatic (yellow) plants were located amongst the healthy (green) plants. We found that the virus was transmitted from thirteen symptomless leaves, eight of which remained symptomless over the whole three-week observation period.

Our next step is to determine whether these infectious, asymptomatic leaves are produced by BBTV-infected plants year-round or in a seasonally dependent pattern.

This plantation was poorly managed, with limited de-leafing, providing a sheltered environment for the banana aphids to multiply. De-suckering was also limited, thus providing more susceptible young plants (favoured by the aphid) that are often obscured by the dead leaf skirts. We suspect that the higher aphid numbers along with the higher number than expected of infection sources present as symptomless, infected leaves and obscured, infected suckers, combine to promote and prolong the epidemic.

Remember

• BBTV-infected plants can be infectious prior to development of leaves with symptoms.

• Removing newly infected plants promptly slows the spread of the virus.

• Four-week inspection cycles during the summer months in high disease pressure situations can reduce but may not completely suppress the outbreak.

• Any reductions in inspection frequency will allow the epidemic to take off.

• Plantations need to be well-maintained to limit aphid vector numbers.

• Grower participation in detection and eradication between formal inspections is likely to have a significant beneficial

impact on control.

More information

- Banana bunchy top disease | Better Bananas

- Banana bunchy top | Business Queensland

- Banana aphid | Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland (daf.qld.gov.au)

- Banana bunchy top virus | Department of Primary Industries, New South Wales (nsw.gov.au)

- Banana bunchy top | Australian Banana Growers (abgc.org.au)

This research has been funded as part of the Improved Plant Protection for the Banana Industry Program (BA19002), which is funded by Hort Innovation, using the banana research and development levy, co-investment from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.

Support for the establishment of research sites and identification of infected plants has also been provided through Hort Innovation Project BA21003 “Multi-pest surveillance and grower education to manage banana pests and diseases”.