Natural predators of spider mites

Natural predators are beneficial insects, that actively hunt and consume specific pest species. Spider mites have many natural predators including lady beetles, predatory mites, rove beetles, and predatory thrips. These natural predators need to be protected through conscientious spray programs (avoiding disruptive sprays) and some can be purchased from suppliers for augmentative releases to address spider mite population flares. Here we investigate two of the key natural predators and how they work to control spider mites.

Stethorus

The small, shiny, black mite-eating ladybird beetle or Stethorus is one of the most important predators of spider mites in bananas. Three species of Stethorus occur in bananas, but the main species is Stethorus fenestralis. All three species appear identical to the naked eye and all species are specialist spider mite predators.

Stethorus numbers increase following mite flares, as mites provide ample food supplies that allow Stethorus’ populations to flourish and eventually bring the mite levels back under control. Stethorus are high-density predators, meaning they are attracted to mite hotspots. Interestingly, both adult and larval Stethorus beetles primarily feed on mites, making them very effective predators against these pests.

The life cycle of Stethorus

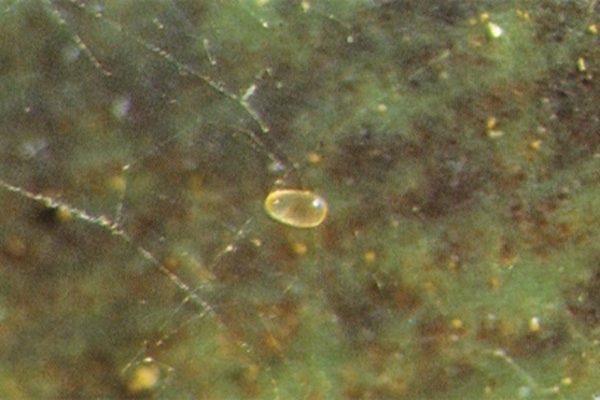

There are four distinct stages in the life cycle of Stethorus and it is important to recognise each of these stages. The elongated, translucent to pale brown eggs are laid singly under the leaves, either on or close to the mite colonies. The eggs are about 0.2 mm long and can easily be distinguished from the smaller spherical (and usually more numerous) mite eggs. Mite eggs are not visible to the naked eye, and a hand lens would be necessary to view them in the field.

Larvae are hairy and vary in colour depending on their age. Larvae go through four stages of maturation, each separated by a moult. Young larvae are pale cream becoming dark grey at maturity. Fourth-stage larvae eventually stop feeding when they are about 2 mm long and attach themselves to the leaf where they pupate.

The pupae are black, hairy and about 1 mm long. Pupae may be found anywhere on the underside of the leaf; however, they tend mostly to be found close to or on the midrib. The pupal stage is easily seen on a leaf, as a skin remains after the adult emerges. To determine whether a pupa is alive or is simply an empty pupal skin, smear it gently with a finger. A wet streak will indicate it was alive and if no wet streak is produced, then it was an empty skin.

Adults are shiny black, almost circular beetles about 1 mm long. They also occur on the underside of the leaf. Where there is a high incidence of mite infestation, there may be more than fifty adults under one leaf, although there are usually less than ten when mite populations are in check.

Looking after your Stethorus population

Broad spectrum insecticides are a major cause of mite flares because they destroy beneficial predators like Stethorus. Avoid using these chemicals (e.g. products containing bifenthrin) to control mites. Check your leaves to see if you have Stethorus present and get a gauge on the population levels. Although research specifically in bananas hasn’t yet been undertaken to determine how many Stethorus need to be present to control spider mites, they can keep spider mite populations in check when spider mite pressure is low.

Californicus

Some predatory mites are commercially available for purchase to apply in the field. The more common predatory mite species Neoseiulus californicus (‘Californicus’) is described as an ‘aggressive and robust mite’.

Californicus mites are less than 1mm long and are pear-shaped. Their colouring is dependent on diet but can be clear to pink or orange. Eggs are clear to white, oval-shaped and similar to that of the eggs of the two-spotted spider mite, but distinctively larger. Females can lay up to 4 eggs per day, eggs tend to be laid on the underside of the leaves along veins or on leaf hairs.

Adult Californicus can consume up to 5 adult spider mites daily and can live for up to 20 days. These beneficial insects can even flourish even when prey is scarce, as they are also able to consume alternate food sources such as pollen or other small insects. However, research has shown that reproduction and developmental rates are increased when Californicus exclusively feed on spider mites.

Californicus is known for its resilience to differing environmental conditions. They remain active in both warm and cool temperatures and can survive well in both high and low humidity better than most other predatory mites. However, their optimal conditions are between 16-32˚ C with a relative humidity range of 40-80%. In optimal conditions (30˚ C), their lifecycles can be as fast as 4 days, almost twice as fast as that of their prey. Californicus are also less sensitive to pesticide residues which enables faster re-establishment after chemical applications.

The use of predatory mites as a biological control for spider mites has been trialled on commercial banana farms in Far North Queensland. Some growers release the predatory mites monthly as a preventative treatment for mite flares. For more details on how to release and release rates, contact a commercial biological service provider. The Association of Beneficial Arthropod Producers Inc. has a list of Australian suppliers.

For more information contact:

The Better Bananas team

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

South Johnstone

Email betterbananas@daf.qld.gov.au

This information is adapted from: Pinese, B., Piper. R 1994, Bananas insect and mite management, Department of Primary Industries, Queensland

This information has been prepared as part of the National Banana Development and Extension Program (BA19004) which is funded by Hort Innovation, using the banana industry research and development levies and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture. The Queensland Government has also co-funded the project through the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.